The Photian Schism: A Clash of Power Between Rome and Constantinople

Introduction

The use of theology to divide Christ’s body has often been a tool in the Pope’s hands. Even today, the Christian world still suffers from the results of these power struggles. From the Council of Chalcedon and Pope Leo I's vision of a centralized Church under Rome, theological disputes have frequently been wielded as political weapons rather than purely matters of faith.

Whether one supports or opposes the theological developments of these councils, the results have been the same: division, hostility, and endless struggles for power. One of the most serious conflicts between the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church—and by extension between Catholicism and all Orthodox families, both Eastern and Oriental—is the controversy over the Filioque clause.

The Rise of the Filioque

The Filioque controversy first appeared in 589 AD at the Third Council of Toledo. Spain was still fighting the influence of Arianism, which claimed the Son was created and not divine. To defend Christ’s divinity, the Latin Church added the phrase “and the Son” to the Nicene Creed.

Originally, the Creed had said the Holy Spirit “proceeds from the Father.” Now, the Spanish version said the Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son.”

At first, this modification stayed within Spain. Over the next two centuries, however, it spread throughout the Latin West.

The Photian Schism Begins

Around 200 years later, Patriarch Photius of Constantinople condemned the Filioque as a corruption of the Nicene Creed, calling it a heretical innovation. This condemnation sparked the Photian Schism (863–867 AD)—a major conflict between Rome and Constantinople.

But was this really only about theology? Or was theology being used as a tool for something bigger? Looking at the historical context of 810–891, it becomes clear that the Filioque was less about belief than about power, authority, and political control.

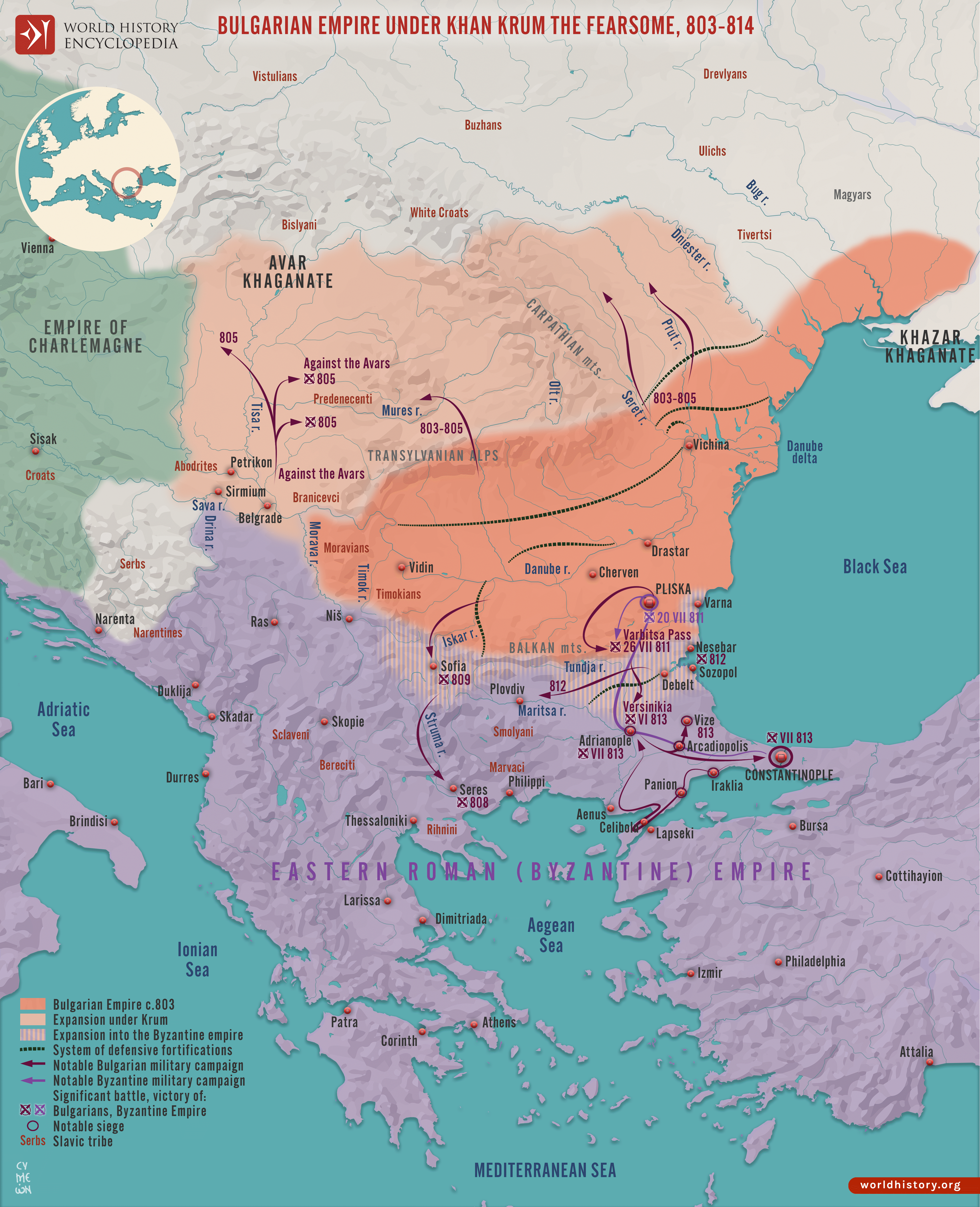

Since the Alexandrian Popes had been removed from leading the Ecumenical Councils after 451, the struggle for dominance shifted to Rome and Constantinople. Both patriarchates competed fiercely, especially over newly converted lands like Bulgaria.

Ignatius vs. Photius

In 858 AD, Emperor Michael III deposed Patriarch Ignatius of Constantinople and replaced him with Photius, a brilliant layman who was quickly ordained and elevated to the patriarchal throne.

Ignatius had criticized the emperor’s uncle Bardas for immoral behavior, angering the imperial court. His removal sparked outrage among monks, who opposed state interference in Church affairs.

When Photius wrote to Pope Nicholas I to inform him of his appointment, the Pope rejected his legitimacy and demanded the reinstatement of Ignatius. In 863, Nicholas excommunicated Photius, declaring Ignatius the rightful patriarch. This escalated the conflict between Rome and Constantinople.

Bulgaria: The Real Prize

At the same time, Bulgaria had recently converted to Christianity, and both Rome and Constantinople wanted to control its Church. Pope Nicholas I sent Latin missionaries into Bulgaria, bringing with them Roman practices—including the Filioque.

Photius seized the opportunity. He accused the Latins of spreading heresy and corrupting the faith. He wrote letters to the Eastern patriarchs, warning that the Filioque distorted the Trinity and blurred the distinctions between the three divine persons.

By defending orthodoxy, Photius also secured Byzantine influence over Bulgaria. His strategy worked: Bulgaria sided with Constantinople, strengthening the Eastern Church’s control.

Thus, while theology was involved, the real battle was for political power and jurisdiction. The Filioque was the spark, but the fire was rivalry between East and West.

From the Photian Schism to the Great Schism

The controversy did not end with Photius. Almost two centuries later, in 1054, the issue of the Filioque re-emerged as one of the key causes of the Great Schism.

Patriarch Michael I Keroularios of Constantinople took a hardline stance. In 1052, he closed all Latin churches in the city, criticizing Roman practices such as:

- using unleavened bread in the Eucharist,

- forbidding married priests,

- fasting rules, and

- of course, adding the Filioque to the Creed.

Some voices, like Peter of Antioch, suggested compromise: if Rome removed the Filioque, the other issues could be set aside. But most Byzantine clergy rejected this. To them, Filioque was not a minor mistake but a serious heresy.

The Bigger Issue: Papal Authority

Behind the theology lay an even deeper disagreement: papal authority. The Pope claimed universal jurisdiction over all Christians, including the Patriarch of Constantinople. The Byzantines rejected this outright, insisting that the Pope was only “first among equals.”

This clash of authority became one of the greatest reasons for the final split—and remains unresolved to this day.

Conclusion

The Filioque began as a defense against Arianism, but by the time of Photius, it had become a symbol of Rome’s ambition to dominate the universal Church. Photius and later Keroularios saw it as an opportunity to resist Rome’s growing influence.

Theological debate was real, but theology was also used as a political weapon: to win Bulgaria, to assert jurisdiction, and to strengthen power. The tragedy is that what should have been about truth and faith turned into a struggle for dominance.

Even today, the Filioque remains one of the most sensitive issues in Catholic–Orthodox relations. It is both a theological problem and a historical wound. While doctrine divides, history shows us that the politics behind it may have done even more damage to Christian unity than the theology itself.

Sources

- Chase, Frederic H. Review of The Photian Schism: History and Legend, by Francis Dvornik. The Harvard Theological Review 42, no. 4 (October 1949): 285–287. JSTOR.

- Rill, J. R. The Photian Schism, 866–867. In Pontificia Graeca. Paris: Garnier Frères, 1900. CX, 741–742. Also in Patrologia Latina. Paris, 1852. CXIX, 1152–1157. Translated by the Monks of St. John’s Abbey.